Dear Reader,

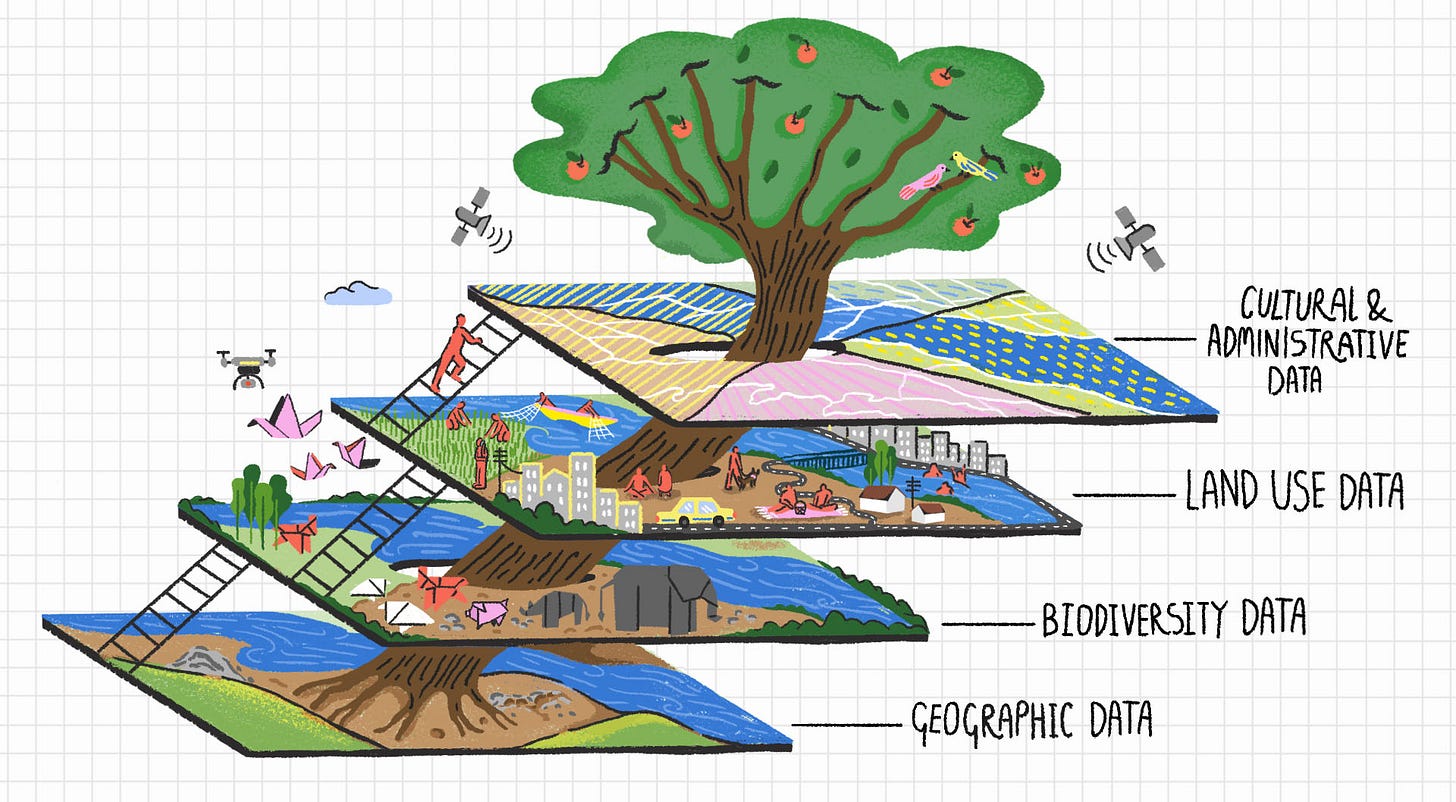

Satellite imagery, drones, IoT devices, remote sensors, and GPS-enabled devices generate rich geospatial datasets, allowing us to map the interplay of naturally occurring and human-made phenomena to a specific time and place. In an Ecologies of Entanglement interview, electrical engineer turned hardware and software developer, Agnes Cameron notes how this technology of seeing — so rich in information and zoomed-out in scale — can add to despair and dread as we witness the beginnings of environmental collapse. But this data also offers new vantage points from which to see some of humanity’s most complex problems.

The integration of AI and machine learning with Geographic Information Systems (GIS) is transforming how we analyse complex geospatial data, opening new opportunities for climate action. For example, Geospatial Foundation Models (GeoFM) are designed to process diverse datasets effectively. With improvements in access to geospatial data and tools, innovation is picking up. Initiatives like HOTOSOM sustain and use open-source mapping tools and data to aid humanitarian response.

But open source also carries risks of misuse and privacy violations. And, simply providing access to data is not enough. Geospatial data is complex and requires skills, resources, and training programs like NASA’s ARSET to promote meaningful use for environmental justice. Without guard rails to protect vulnerable groups, biased or poorly contextualised data can harm communities. Much like the paper maps of the past, contemporary geospatial data infrastructures are ways of seeing shaped by power relations, enabling states and private entities to map land and resources for governance and profit.

In this issue, we descend from the 30,000 ft view of a satellite and land on the ground in Asia, where we’ll explore pathways through GeoAI towards equitable environmental and social outcomes.

Spotlight: Disaster Response, Prediction, and Mitigation

In Asia, a region characterised by extreme weather events, disparities in the state of critical infrastructure, and inadequate access to appropriate early warning systems, the use of GeoAI has the potential to establish reliable systems of disaster response and management.

For example, Indonesia-based Peta Bencana builds flood risk maps, leveraging geospatial data, crowdsourced social media data, and validations by government agencies.

Researchers in Bangladesh propose using AI for tropical cyclone prediction. Graph Neural Networks (GNN), a deep learning model that works with graph data, are great for capturing complex interactions between atmospheric and oceanic datasets. Trained on historical satellite data and field observations, GNNs can predict cyclones from past wind flows and cyclone formation patterns. However, researchers note that GNNs are complex, difficult to train and require cross-field expertise to adopt.

The lack of credible data poses another challenge. While good data sets exist on basic rainfall, temperature, humidity, and wind speed parameters, there is a lack of granular, localised data in many regions. Data on social, economic, and health factors also remain incomplete, making it difficult to predict disease outbreaks or create efficient warning systems.

Curated Reads

In this section, we look at the data infrastructures that inform GeoAI, their role in environmental justice, and strategies for Responsible GeoAI.

Context Matters: State Power & Data Infrastructures

The digitalisation of maps is an ongoing process for many parts of Asia, as governments transfer paper-based land records to mapping software. Through a comparative analysis of One Map projects in Indonesia and Myanmar involving the consolidation of geospatial data onto digital platforms, authors embed the trajectories of these projects in unique political and historical contexts. They track the success of the project in Indonesia — attracting both foreign funding and domestic support — due to its rich history of counter-mapping in defence of indigenous lands, its established democracy, and its focus on climate mitigation in forest monitoring. In contrast, Myanmar's narrower focus on domestic policy reform, combined with bureaucratic resistance and the 2021 military coup, led to the project's failure.

Counter Mapping to document Indigenous land use

Top-down mapping initiatives have a legacy of negative impacts on community land rights and resource management practices, prompting communities to adopt their own cartographic methods such as counter-mapping. Increasingly, handheld devices such as sensors, drones, GPS trackers, and easy-to-use GeoAI software are simplifying the collection of community data (oral histories, local landmarks, and generational land use) and correlating it with available spatial data (hills, rivers, forests) - thereby democratising the process of mapmaking.

The expansion of community-led counter-mapping practices into the digital realm makes GeoAI a critical tool to protect native lands from ecological destruction. For example, Indigenous people in the Malaysian state of Sarawak, on the island of Borneo, are turning to such mapping technologies to formally establish their land rights and resist the expansion of palm oil plantations in their territories. These community-made maps have even been presented as evidence in ongoing litigation for previously undocumented native land rights to be legally recognised and thus protected for generations to come.

Critical Remote Sensing & Environmental Justice

Critical remote sensing has emerged as a counterpoint to extractive uses of satellite data in environmental justice struggles. Through affordable IoT kits, citizen scientists can collect data to establish their own evidence base. Following citizens deploying CitizenSense kits near rural fracking sites in Pennsylvania, filling gaps left by government air quality indices, authors argue that while this data may not meet regulatory standards, this diverse, frequent collection produces “just good enough data” when combined with official measurements to demand legal accountability.

An excellent guide for those interested in focused applications of remote sensing for environmental justice, this socio-technical framework identifies key open-access resources to support ground-level stakeholders, for efforts in water management, timber extraction, food production, and fossil fuels use. Authors argue that through knowledge sharing and expanded access to resources, remote sensing data infrastructures can (and should) be adapted to expose environmental injustice.

To be open or not - resolving inherent tensions

While aiming for transparency, open-access data also presents privacy and misuse risks. In this interview, Finnish experts highlight that geospatial datasets can include sensitive information about critical infrastructure, creating vulnerabilities to physical attacks. They then recommend using a risk assessment matrix and implementing a process to evaluate risks before releasing geospatial data publicly.

Purpose-oriented data releases are another way of preventing data misuse. In Norway, the International Climate and Forests Initiative (NICFI) Satellite Data Program, provides commercial satellite imagery covering the world´s tropics for non-commercial applications specifically for climate action, like reducing and reversing the decline of tropical forests. Such approaches are particularly relevant for Asia, which is increasingly seeing government-led open data initiatives.

Doing Responsible AI with geospatial data

In their systematic review, Marasinghe et al. emphasise the need for human-in-the-loop and participatory approaches in leveraging GeoAI, especially in urban settings. Given the vulnerability of Asian cities to climate change and the growing use of GeoAI for monitoring and early warning systems, the article’s proposed Responsible AI framework offers valuable guidance for policymakers and researchers.

The authors caution that GeoAI systems, which often rely on visual data to assess built environments, can produce inaccurate or unethical results if local context, such as cultural or ecological factors, is overlooked. They emphasise the importance of involving diverse stakeholders, including local communities and experts, in the design and implementation of GeoAI to ensure these tools meet the specific needs of the communities they serve. This resonates with the findings in another pre-print, where the authors highlight the value of multi-stakeholder perspectives in data labelling. Labelling, the process of categorising real-world phenomena into distinct classes or groups, is highly context-specific. Therefore, it requires regional expertise and knowledge, and is ideally coordinated with local experts.

On our Radar

Globally, we are seeing a lot of interest in using Foundational Models (FM) on multi-modal geospatial datasets for environmental monitoring. For example, Hong et al. developed SpectralGPT, a universal remote sensing FM that can handle images in ultraviolet, infrared, various sizes, resolutions, time series, and regions; useful for crop health or deforestation monitoring.

Last year, IBM and NASA jointly launched their first open-source geospatial FM for Earth observation data. Built using NASA's Harmonised Landsat and Sentinel-2 dataset, it has been applied to flood mapping, with significant accuracy using smaller samples. It also aids burn scar identification, crucial for active fire management and post-fire recovery efforts.

In a vision paper on GeoFM, researchers note that task-agnostic large language models (LLMs) can sometimes outperform task-specific, fully supervised models in zero-shot or few-shot settings. However, for other geospatial tasks involving multiple data types like street view image noise classification and remote sensing scene classification, current FMs lag behind specialised models.

Around the web

Navigating GIS: A guide by Cathy Richards to make responsible mapping more accessible for environmental justice organisations.

Counter Mapping: In this documentation, the Zuni People counter Western notions of place and geography by bringing their Indigenous voices to map creation.

Indigenous Communities & Mapping: Hear Michael Jok from Borneo speak about how Indigenous communities in Malaysia are using GIS to assert land rights.

Data Dialogues: Interested in the complexities of environmental data? Tune into this podcast series by Open Environmental Data Project for learnings & reflections from the ecosystem.

Our next podcast episode is out! Cindy Lin, an ethnographer working on critical data studies and environmental governance, and Sherif Elsayed-Ali, with a career spanning from human rights to Climate AI entrepreneurship, reflect on the current noise around the potential of AI for climate action. Highlights from the episode include:

In the best use-case scenarios, AI could help optimise existing processes such as cement manufacturing to reduce emissions;

Developers often overlook externalities like energy or water requirements;

Sometimes “collective restraint” can spur innovations in ‘small’ infrastructures;

All AI is not built equally - some consume more energy than others.

Tune in as experts break down some of the myths of Climate AI and the systems that sustain them.

Our upcoming newsletter editions look at AI applications for conservation as well as the environmental impacts of this technology. For our readers working or interested in this space - what innovations or emerging use cases are you excited about? What are you reading? Email codegreen@digitalfutureslab.in to share your ideas for our next issue.

Credits

Research and curation: Dona Mathew, Meredith Stinger, Tammanna Aurora | Illustrations: Nayantara Surendranath | Art Direction: Tammanna Aurora | Layout Design: Shivranjana Rathore