Issue 08: Smart and Sustainable Cities?

Exploring Asia’s Data-Driven Urban Futures

Dear Reader,

Asia's cities are vibrant, dynamic, and often full of contrasts. Images of Tokyo and Taipei, for instance, show shiny skyscrapers and high-speed rail networks co-existing with ancient temples and historical landmarks. However, these urban landscapes and their residents are increasingly under threat from the rapidly accelerating impacts of climate change — rising sea levels, urban heat island effect, and air pollution jeopardise livelihoods, biodiversity, public health, and food security.

Fast-paced urban migration is also placing significant pressure on urban governance. By 2030, it is projected that around 55% of Asia’s population will live in urban areas. Many of these challenges are complex and interlinked. Deforestation driven by urban expansion reduces vital carbon sinks, worsening climate change and degrading biodiversity. This, in turn, leads to lost ecosystem services and reduced resilience to further climate impacts.

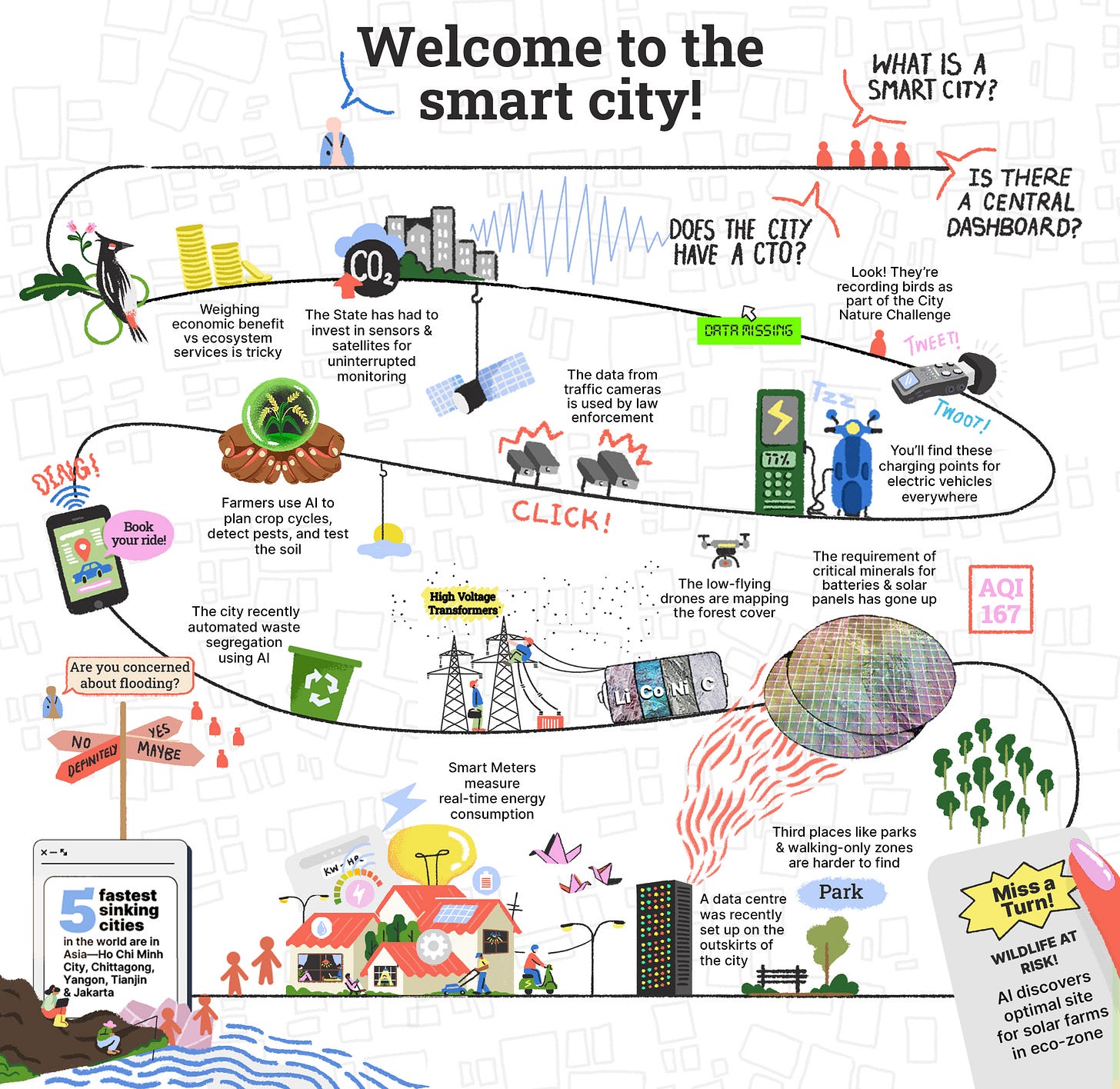

As governments across the region prioritise the creation of climate-resilient and sustainable cities, digitalisation is emerging as a key driver in national urban strategies. The concept of 'smart cities' is central to this discourse, with advances in AI applications emerging in areas such as waste management and citizen engagement. While these innovations pave the way for more technology-driven cities, they also foster new forms of urban governance, characterised by the increasing corporatisation of city management. AI is also being leveraged to meet Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 11 for cities and communities. A review highlights that while AI enables efficient service delivery and sustainable systems, resource demands and data biases challenge equitable, green, and inclusive development.

Modern cities are intricate webs of interconnected domains — energy, transport, health, education, law enforcement, and sanitation — each of which must function effectively to enhance the well-being of residents. Given the dual challenges of climate change and rapid urban expansion, the question remains: How sustainable will the cities of the future truly be?

Curated Reads

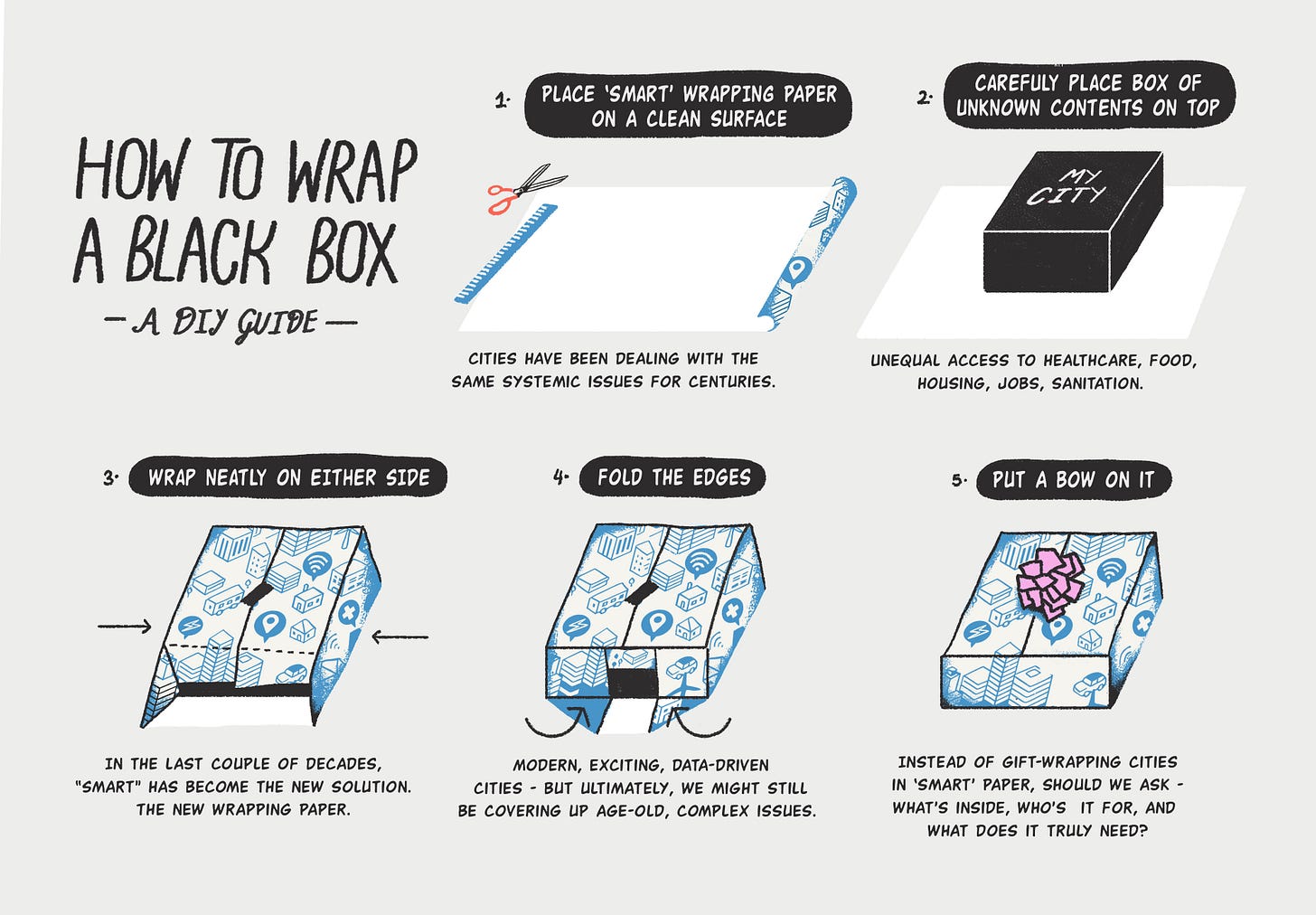

The ‘smart city’ and the ‘sustainable city’ have emerged as distinctive concepts envisioning pathways to green, citizen-centric, urban futures. But how much do these concepts overlap in practice? As AI becomes a central tool in transforming urban landscapes and governance, we examine the potential and contradictions of smart, data-driven, and technology-focused interventions to create sustainable future cities.

The Smart City: New Technologies, Old Dilemmas?

Smart cities utilise interconnected IoT sensors to collect, share, and analyse real-time data for urban planning and governance, from monitoring air quality to traffic management. The smart city concept first emerged in the late 2000s as a form of corporate storytelling influenced by IBM’s Smarter Cities Challenge, and has since become a mainstay of state-led public policy and urban planning. Iterations have evolved over a decade, moving from tech-centred to human-centred conceptions in global discourse. A vibrant and well-developed critique of the numerous inequities these cities of the future may perpetuate and create has emerged alongside this discourse.

The cities of today are ideal receptacles for large flows of different types of capital: financial, physical, human, social, and natural. These authors examine smart cities as a spatial manifestation of 21st-century capitalism, characterised by the accumulation of capital in the hands of a few, complex public-private partnerships for governance and resource extraction, and ubiquitous harvesting, storage, and analysis of data from the natural and physical environment as well as from human behaviour and interactions.

A study analysing smart city mission policy documents in India reveals how national strategies often borrow heavily from global rhetoric on smart cities. These documents tend to adopt a top-down approach to urban development, using prescriptive language and abstract imagery. Citizens in these documents are represented by interchangeable stick figures, illustrating a reductionist view of urban life. Furthermore, the concept of citizenship is often tied to accountability, entrepreneurship, productivity, and business improvement, while overlooking the complex, multi-dimensional realities of urban living. In these narratives, citizens are generally portrayed as a homogenous group, expected to be both entrepreneurial and tech-savvy, reflecting an idealised vision of the smart city.

In a separate paper, authors exploring the idea of just smart cities in the Global South highlight the lack of theoretical frameworks addressing the unique challenges of these regions, emphasising the need to explore what 'the right to the smart city' means in this context. They build on the framework of 'expose, propose, and politicise' to suggest a research agenda for scholars to move beyond the current case study approach that dominates smart city literature. The authors argue that research should begin with ‘expose’ – examining who is excluded or marginalised by smart city initiatives, moving towards ‘propose’ by working with those affected to advocate for alternate visions of the smart city, and finally, ‘politicising’ these as the fundamental absence of rights which must be addressed. They call for more action-oriented research that focuses on the grassroots resistance led by citizens, NGOs, and community data intermediaries who are working on the front lines to challenge the status quo.

The Smart City — Smart Data Nexus

Data-driven planning and governance are key aspects of the promise of smart cities to surface and address residents’ needs. OECD’s report on smart city governance highlights initiatives that centralise and visualise urban data to produce real-time inputs for city planning, such as Seoul’s Open Data Plaza and Japan’s Sketch Lab. However, a lack of financial resources, data management skills, data security, and fragmented datasets across the government and private sectors hinders effective data use and sharing. In Thailand, citizen-facing apps like Traffy Fondue allow reporting by citizens on traffic conditions, and could help urban planners and local authorities address traffic issues in real-time. However, research shows that a lack of skill and capacity in local government leads to under-utilisation of data for decision-making, with data primarily being used for documentation and reporting. To foster greater transparency and empower citizens, upskilling government officials and providing data literacy programmes for citizens are critical.

According to this report, data representativeness and data quality are key concerns in equitable urban planning, and may reinforce biases and exacerbate existing social inequalities. But increased data representation isn’t a straightforward solution for those living in informal settlements, who may face increased risks of displacement by being visibilised through new forms of data collection. In cities like Hyderabad, India, for those living in informal settlements, fears of displacement have become attached to digital data collection processes. As digital technologies are more widely employed for urban governance, claims to commodified urban spaces have become more precarious, along with growing distrust in data collection processes.

This author identifies ‘data dignity’ as fundamental to smart city technologies — the notion that individuals maintain sovereignty and self-determination over information linked to their identities. Advocating for the ‘recoding’ of the smart city stack (consisting of networked sensors, data platforms, AI/ML models, and automated control systems), a system of open standards, decentralised cloud infrastructures, and community-governed oversight would rein in unchecked extraction and commodification of citizen data.

Code-Smart or Climate-Smart?

SDG 11 focuses on safely and sustainably supporting expanding urban populations through smart, resilient, and culturally-informed urban planning.

In a review of literature at the intersection of SDG-11 and smart city projects, authors argue that while environmental sustainability is a necessary aspect of achieving broader goals highlighted in SDG-11, social and economic sustainability are often prioritised over environmental sustainability in smart city initiatives. Potential externalities and environmental impacts, such as increased energy demands, are underexamined. Moreover, they highlight how critical smart city literature often speaks to environmental and social considerations in these projects in a mutually exclusive way, recommending that future research embrace an expanded sustainability framework that includes both social and environmental aspects together.

A key target (11.6) under SDG-11 is to reduce the adverse per capita environmental impact of cities, focusing on air quality, and municipal and other waste management. However, while the use of ICTs in cities has potential for emission reductions, there is a danger of a rebound effect of efficiency gains, in which expanded ICT use will drive up emissions and material impacts, curtailing environmental gains. These authors argue that this demands an expanded lifecycle approach to understand the sustainability trade-offs in smart cities. In a lifecycle analysis of smart cities and ICT development, authors highlight a gap in research empirically demonstrating increased environmental sustainability in smart cities. Rather than overtly focusing on energy efficiency, optimising transport, and waste management through technology, they recommend a turn towards low-tech urban solutions and a holistic approach that incorporates the social, economic, and environmental dimensions of urban development in smart city planning.

Towards equitable urban AI applications

Recognising a lack of sector-specific ethical frameworks for AI in urban planning, this research proposed 14 principles to guide the development of Urban AI applications. These principles address concerns like human agency, data privacy, transparency, fairness, and algorithmic bias, all crucial for equitable AI integration in cities. The framework emphasises the importance of inclusivity, ensuring AI advancements benefit marginalised communities and reduce inequalities. It also calls for adaptive governance to keep pace with rapid technological change and for ongoing interdisciplinary collaboration to address urban-specific challenges. While offering a foundational structure, the authors encourage further research and adaptation, especially concerning the socio-political, spatial, and cultural dimensions of urban AI. Future studies should focus on refining these principles, ensuring ethical AI deployment that enhances urban living while mitigating risks.

Spotlight: Multispecies Justice

How are bees experiencing the city? This is one of many questions municipalities and communities in Costa Rica’s ‘Sweet City’ are asking as they explore ways to prioritise biodiversity, multispecies interactions, and the collective design of socio-ecological urban spaces. Reflecting a growing “more-than-human” turn in nature-based solutions (NbS), emerging scholarship calls for multispecies justice, recognising the needs of humans, animals, rivers, and ecosystems while equitably distributing risks and benefits across social, spatial, economic, and environmental dimensions.

Moving beyond human-centric urban planning, a de-anthropocentric NbS approach promotes coexistence, ecosystem integration, climate education, inclusive governance, and green innovation. Examples like Singapore’s Binhai Bay Garden City, with its intelligent irrigation and real-time environmental monitoring, highlight how technology can support both human and ecological well-being.

AI can potentially aid in scaling NbS through tools like AI-generated visions of future nature-positive cities, but challenges remain. Limited data quality, opaque algorithms, and overreliance on quantitative outputs risk sidelining indigenous knowledge, social values, and transparency in decision-making. As cities in Asia grow, balancing technological advancement with ecological and cultural sensitivity is essential.

Around the Web

Feral Atlas: Explore the connections between human-made infrastructure and the ecological transformations it affects.

Multispecies Cities: Solarpunk Urban Futures: A collection of stories that examine our relationship with the more-than-human. (Solarpunk is a science fiction subgenre).

City-Game Database: Try your hand at city-making and urban planning.

Data Justice in Practice: A Guide for Impacted Communities: Actionable information for communities to implement data justice principles and practices.

The great abandonment: what happens to the natural world when people disappear? Read on to find out an under-explored impact of urban migration.

Tuning in…

In the latest episode of Code Green, ChengHe Guan and Raj Cherubal examine the role of data and AI for creating smart and sustainable cities in Asia, sharing their distinct experiences from Shanghai and Chennai. A sneak peek here!

Note to readers!

This is the second-to-last issue of our newsletter! We've loved curating these monthly dispatches for you. As we plan the next chapter and look for ways to keep the Code Green community thriving, we’d love your input: What articles or topics resonated with you? What would you like to see more of? Drop us a note at codegreen@digitalfutureslab.in — your ideas might just inspire what’s next!

Credits

Research and curation: Dona Mathew, Meredith Stinger, Tammanna Aurora | Illustrations: Nayantara Surendranath | Art Direction: Tammanna Aurora | Layout Design: Shivranjana Rathore