Issue 09: Curb your enthusiasm!

Reflections on techno-optimism in climate governance

Dear Reader,

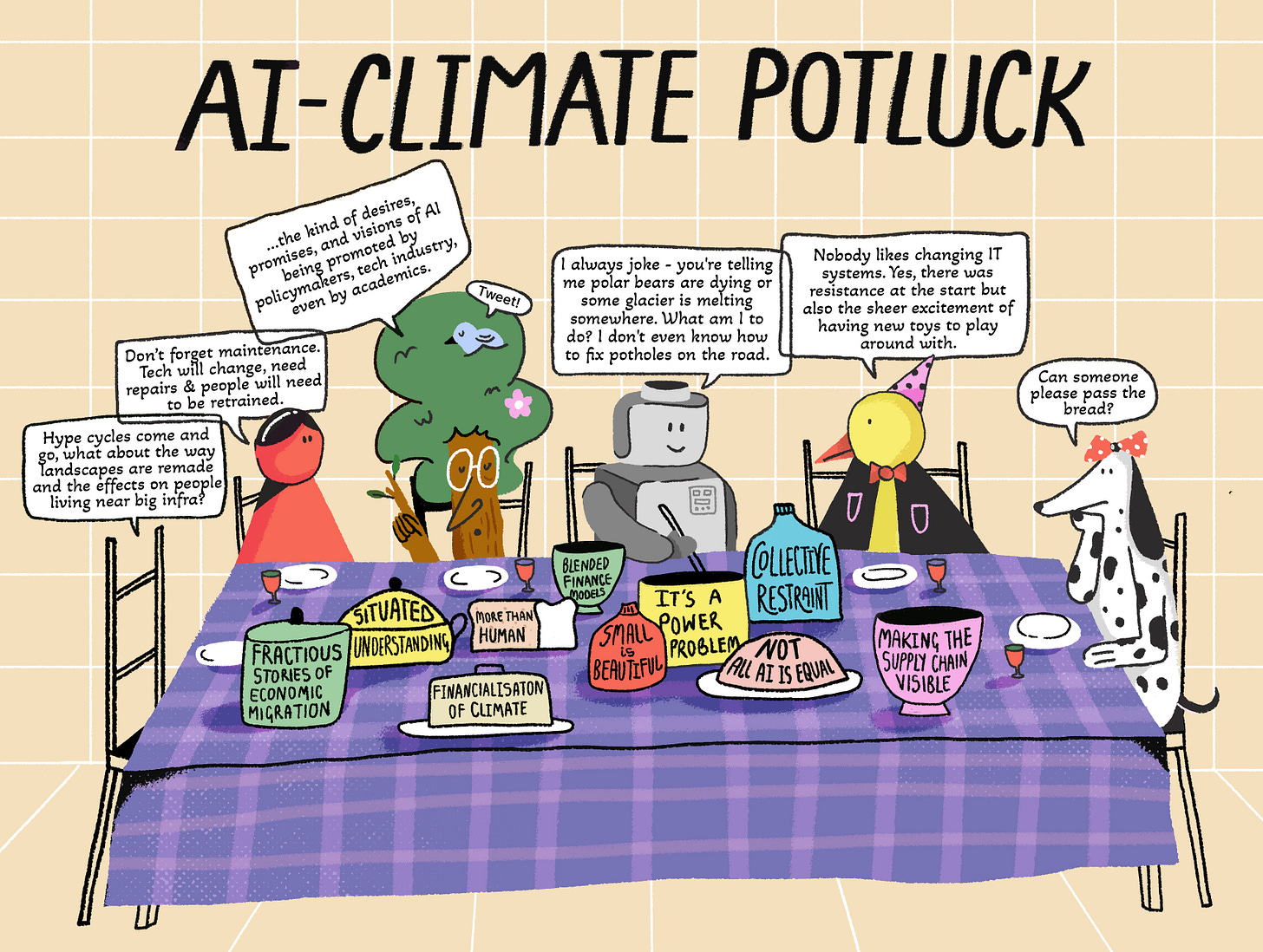

In May this year, the Indigenous Environment Network called for a moratorium on all false solutions for the climate crisis. A powerful wake-up call, they point to a troubling truth: over the last 20 years, green economy approaches that hinge on carbon markets, pricing, and offset mechanisms have proven ineffective in reducing emissions. With decades of not moving the needle, we must examine what isn’t working. Luis Murillo, in our latest podcast episode, points to the “fundamental tension” embedded in the financialisation of the climate space, “If you have capital as the engine for that space, and capital is at the source of environmental degradation, historically speaking, that led us to where we are right now.”

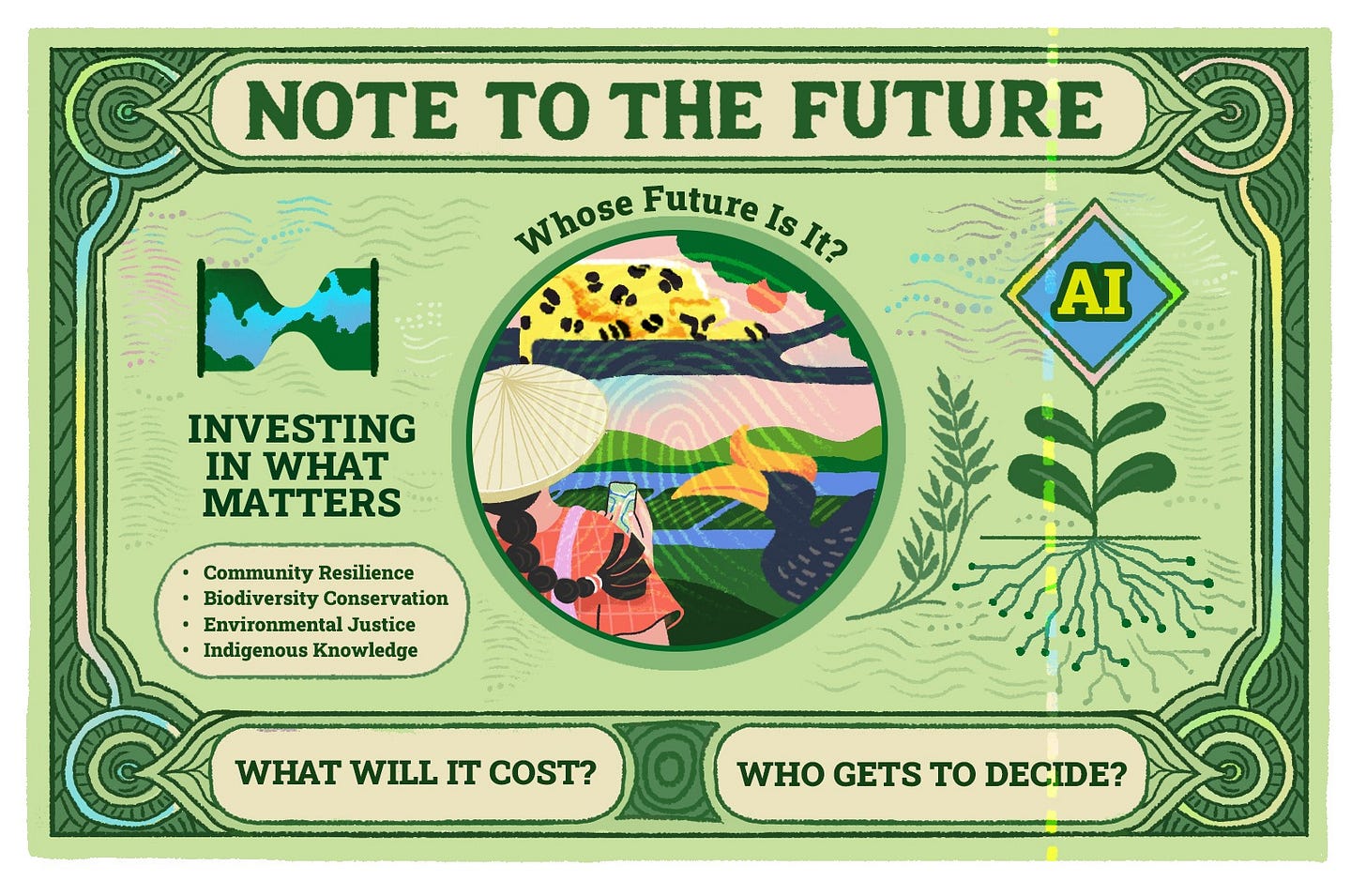

In this final dispatch of Code Green, we zoom in on a common thread across our series—in an increasingly tech-centric climate action discourse, what big picture are we missing? Throughout, we’ve worked to identify the potential and challenges for pathways towards safe and trustworthy Climate AI. And yet, what futures are being wrought by dominant narratives, politics, and powerful interests steering the climate-tech innovation and investment space?

Achieving net-zero in Asia will require an estimated $70 trillion investment between 2023 and 2060. However, geopolitical shifts are creating uncertainties in the climate finance landscape, with far-reaching consequences for vulnerable regions. The United States has cancelled $4 billion in funding for the UN Green Climate Fund, withdrawn a 2023 $17.6 million pledge from the UN loss and damage fund, and exited the Just Energy Transition Partnership, a multilateral platform meant to accelerate the phase-out of fossil fuels in South Africa and Asia.

According to a UNESCAP report, few countries across Asia are on track to meet GHG emissions targets. Funding remains highly concentrated in countries like China, India, and Japan. Least Developed Countries (LDCs) in the region received only 2% of international climate finance from 2021 to 2022. Beyond allocation issues, equity of fund distribution is a concern, with only 51% of Southeast Asia’s adaptation funding distributed from 2017 to 2021.

Within this complex ecosystem, investments in AI are expected to reach $110 billion by 2028. However, unequal access to AI tools, data, and resources between high-income and low-income regions poses a significant risk of deepening existing inequalities. According to the 2021 GPAI report, poorly-directed funding could lead to AI’s rapid growth becoming a distraction or a cause of societal harm. How much of this focus on AI is causing harm or distracting from essential climate funding needs?

The AI-climate intersection must avoid exacerbating inequities, particularly as attention turns to "silver bullet" solutions that may prove economically or socially unviable. Amidst intensifying climate impacts, we ask what structural changes are required to enable equitable, inclusive, and sustainable futures?

Curated Reads

Innovative mechanisms like green patents are emerging as signposts for private financing of green technologies. However, in climate-vulnerable contexts in the Global South, bottlenecks such as digital infrastructure gaps and limited data quality and availability may create additional barriers to access competitive funding sources, such as Grand Challenges. However, is a focus on financing, innovation, and efficiency of Climate AI enough to address the climate crisis?

Drivers of innovation and investment

In our analysis of the AI and climate financing domain, we came across factors that seem to be driving the adoption of AI solutions for climate on one hand and pushing for more investment in AI solutions for climate on the other.

We’ve seen a growing focus on climate solutions in AI open calls more broadly. For example, this year’s AI Action Summit announced a call for AI projects for well-being and ethical use, selecting 50 projects, of which 9 were related to climate and nature. Of these, 7 were from countries in the Global South.

In a recent assessment of grand challenges for AI, climate, and nature, the authors highlight the value of these funding models to centre climate challenges, using AI as a means to solve them, with sometimes the final output not using AI at all. However, they note that a majority of GCs emerge from the Global North, and recipients are also skewed to this region. They also note that GCs are not the only way to fund climate issues, calling for a blend of funding and open innovation models like grants, incentives, hackathons, and incubators, depending on the stage of innovation.

As we’ve highlighted in previous issues, Green AI is gaining traction as a way to centre resource efficiency in AI model development, and a combination of patenting green technologies and open-source could potentially drive private investment in this area.

Researchers are pointing to the environmental and technological potential of TinyML—ultra-low-power AI, exploring how combining patent protection with open-source collaboration can accelerate innovation in green AI. Patents offer competitive and economic advantages, with recent research from the UK and EU suggesting that they may boost VC funding probability by up to 20%, while open source fosters transparency, community input, and rapid adoption. The synergy of both is expected to drive efficient, scalable climate solutions, but findings vary by geography and investor type, cautioning against overgeneralisation.

Models like TinyReptile, compression algorithms, and benchmarking frameworks demonstrate practical progress in less resource-intensive AI. Cross-sector collaboration, talent development, open patenting, and standardisation are essential for advancing TinyML in environmental governance.

But what’s the cost of climate-tech innovation?

Global trends, with possible impacts in Asia, indicate that there is impending investment and innovation potential in climate-tech. As Hanyuan Wang notes in our new podcast episode, climate schools are emerging across the region, incubating the next generation of tech innovators. While these trends are encouraging in the context of developing solutions for the ongoing climate crisis, how impactful will this reliance on the promises of climate-tech innovation actually be?

Current discourse on climate-tech applications indicates a strong flow of ideas from the Global North to the Global South, risking technology transfers that are not contextualised to the needs of climate-vulnerable countries. For instance, carbon removal technologies have been gaining prominence in climate strategy literature. However, knowledge building is primarily happening in the Global North. The author of this study writes that carbon removal technologies must be integrated into sociotechnical systems with attention to justice, governance, and equity, particularly for the Global South. Historically marginalised, these regions face risks from exploitation tied to carbon offset markets, extractive industries, and weak regulatory capacity. Procedural equity and inclusive governance are vital to ensure fair participation in technology design and deployment. Yet, climate assessments and funding remain skewed towards Global North priorities. There is a pressing need for collaborative research, co-designed innovation, and capacity-building in the Global South to align carbon removal with local needs and uphold the Paris Agreement’s equity principles, especially CBDR-RC (Common but Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capacities).

For advanced technologies like AI, even as community-led, participatory climate solutions are prioritised, and funding is directed towards building the necessary data and digital infrastructures for eco-innovation, what ends do these climate solutions meet?

Curbing techno-optimism, nurturing systemic change

Climate technology entrepreneurship is essential, but on its own, insufficient to address climate change and the excessive demands on natural ecosystems that far outpace regenerative capacities. An over-reliance on technological solutions may delay necessary systemic changes, especially since their development uses more resources than efficiency gains can offset. We’ve referenced Jevons Paradox before—where increased efficiency inevitably leads to greater resource use—a concept more and more relevant to AI growth conversations. Discourses on planetary boundaries are missing from current entrepreneurial ecosystems and mission-oriented innovation policies, which are obsessed with competition and growth. Research indicates a positive correlation between countries that rank higher in digital entrepreneurship and energy consumption—they are often the biggest contributors to climate change.

Given the urgency of the climate crisis and the focus on digital interventions, entrepreneurs in Asian countries need supportive systems that provide capacity building and training in climate issues, finance to underwrite solutions that minimise resource and material dependencies, and policies to balance economic development with climate action.

Structural changes to climate action policies are integral to decouple resource-intensive technology innovation from economic growth. This study examines techno-optimism in international climate policy through two prominent climate-tech solutions: EVs and Bio-energy and Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS). EVs, though promoted as green alternatives, rely on the extraction of raw materials like lithium, cobalt, and nickel, often sourced from Africa and South America under environmentally-destructive and exploitative labour conditions. Similarly, BECCS, though marketed as a mitigation tool, demands an estimated 300–600 million hectares for biomass production, raising serious concerns about land rights, biodiversity loss, and competition with food production.

These technologies maintain current unsustainable models, such as car dependency and industrial emissions, rather than challenging their foundations. Reliance on such innovation delays immediate action and misplaces hope in future breakthroughs. Small Island Developing States (SIDS) and other Global South actors advocate for integrating traditional ecological knowledge, community-based resource management, and stronger corporate accountability into international law. Moving beyond growth-centred development models, a more ecological and post-growth approach grounded in procedural equity, local participation, and empowerment is urgently needed to ensure that global climate governance reflects both environmental limits and social justice.

Planter Box

Post-Growth, Degrowth, and AI Minimisation

In our episode on Agriculture, Anubha Singh cautioned us against the harmful effects of fail-fast approaches, often used by tech startups to target farming communities. As the climate crisis deepens and the urgency to find solutions drives rapid growth and innovation, Michael Kwet’s call for digital de-growth feels more pertinent than ever. Responding to US climate and energy policy changes and a ramp-up of global tensions regarding AI dominance, a recent publication from the University of Virginia calls for a global governance shift to AI minimisation, encouraging us to ask, “How much of the solution is also the problem?” The author suggests that moving beyond sustainability metrics susceptible to greenwashing may mean flipping the narrative of technological progress from unlimited growth to minimisation altogether, offering 5 starting points for this shift:

Decrease AI Adoption: AI must be seen as a tool entangled in broader ethical, digital rights, and environmental issues.

Fossil-free AI Infrastructure: AI services and energy sources must decouple from fossil fuels and shift to renewables.

Destruction Assessment: AI must only be used when the benefits outweigh the destruction it causes.

Sovereignty-Focused: Minimisation agendas must promote mineral, technological, geopolitical, and Indigenous sovereignty.

Non-Western perspectives for the AI Agenda: Advancing the AI agenda must come from collaborative knowledge production with non-Western perspectives.

Around the Web

A photo essay documenting the historic Silk Road in this current age of climate change and Digital Silk Road initiatives.

Code Green podcast guest Cathy Richards recently published a Community Data Playbook of environmental data case studies and strategies for data stewards.

Observatory of Planetary Justice Impacts of AI collects, documents, and analyses real-world cases of AI’s impacts on planetary justice throughout the entire AI supply chain.

ICYMI

In our final podcast episode, Hanyuan ‘Karen’ Wang and Luis Felipe R Murillo examine the benefits and shortcomings of AI-driven climate solutions, emphasising the importance of research and funding partnerships, community data stewardships, and recognition of AI’s negative environmental impacts.

Credits

Research and curation: Dona Mathew, Meredith Stinger, Tammanna Aurora | Illustrations: Nayantara Surendranath | Art Direction: Tammanna Aurora | Layout Design: Shivranjana Rathore